Wise sayings on software subjects that can be applicable in deliverables, presentations, arguments etc.

Should I use HTTP status codes to describe application-level events?

On using HTTP as a pseudo-transport OSI layer and embracing the impedance mismatch between

HTTP and a SPA's application layer:

Should I use HTTP status codes to describe application level events

history of the evolution of Internet and IPv4 / IPv6

history-of-ipv4-and-ipv6.pdf.

Y-Combinator discussion: here.

on the need to rewrite software from time to time

source

Code rots, even the best code rots, because the people and cultural environment that the code was written under change and fade away. Refreshing it occasionally, even if it isn’t improved in a significant way, is one way to deal with that rot.

Even if the product/library/framework never changed much, rewrites would still be necessary to keep it going as new generations of programmers shuffle through. Otherwise we wind up with a [...] dystopian culture of software archeology.

Static Typing versus Inference

Using a statically typed language doesnt mean you need to add type signature everywhere, these are languages who lack a good type inference (like java).

In languages with good type inference (ocaml, f#, haskell), the compiler can infer the types, and check your code at compiler time.

The style of programming change a bit with good inference, because you dont use types of arguments to document your code, or specify a behaviour or abstraction. You can create simple functions and compose that, because is not verbose and safe checked at compile time.

[...] It is really easy to confuse statically typed languages with poor type inference (like Java), with others with good type inference (like ocaml). The program is compile checked in both cases, but the code is really different.

public int Add(int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

vs.

let add a b =

a + b

source

JavaScript Evolution

We see a mostly linear progression for the JavaScript community from the days of plain scripts, to adding module systems, to adding compilers, to adding type systems.

source

Essential vs. incidental complexity

Adding a single feature means that you have to figure out how it is going to play with all the other features. That makes the cost of implementing the N+1 feature closer to N than to 1. …

Indeed, these two kinds of complexity feed off each other. If essential complexity growth is inevitable, you want to do everything you can to reduce ongoing accidental complexity.

- Essential complexity is also referred to as "inherent complexity"

- Accidental complexity is also referred to as "incidental complexity" or "unnecessary complexity"

Failing abstractions (or why if thou gaze long into an abyss, the abyss will also gaze into thee)

When people try to fix all the leaks in an abstraction, this usually turn the abstraction into an ugly twin of the stuff it tried to simplify. ORMs are a good example of that.

battling complexity

Noticing how these pockets of complexity lead to those kinds of problems isn't obvious or intuitive, because it's effectively a Butterfly Effect that causes most of its severe repercussions much further down the line.

YAML vs. XML

YAML has more complexity in syntax, but a data model that fits to data structures in programming languages (records/maps, arrays/lists, integers, floats, boolean, bytes, strings). As long as you do not implement a YAML parser yourself (why would you do that?) you should have easy times with YAML.

XML on the other hand is relatively easy to parse, but has a complex data model that maps well just to a DOM. For anything but markup text, you do not have a direct mapping to/from XML.

Rube Goldberg machine

A Rube Goldberg machine is a deliberately over-engineered contraption in which a series of devices that perform

simple tasks are linked together to produce a domino effect in which activating one device triggers the next device

in the sequence.

On Spring framework's failure when it comes to Inversion of Control / Dependency Injection

source

You keep saying "hand rolled framework" while the thing being discussed is a basic factory, I have to wonder if you know what a "framework" is as well. The scenario you describe simply doesn't exist. I "hand roll" my wiring precisely because my projects are big and modular, and I need the control inverted to the application boostrap and not scattered around in vague XML files and annotations.

I write this code because I realize it's the most important aspect of my application - the logic that hooks the parts into a whole exactly as I need and not by random happenstance and type name matching.

When you have a project that largely consists of reusable modules, it's not a smart idea to embed project-specific configuration in annotations on supposedly project-neutral components, don't you think?

When you use annotations and autowiring in Spring, do you realize the very point you seem to stress about, namely inversion of control, gets the knife? Annotations represent inversion... of inversion of control. Information that should be specified outside the object is instead embedded back on it, same as would be the case if you directly instantiated dependencies inside it, or fetched from a global service locator.

Spring doesn't assist IoC, in fact it provides tools which quickly and swiftly destroy it.

Ever needed empty "tag" classes and interfaces? Or qualifier annotations? Tell me, how does this fit into the whole "the object is not aware of its environment" concept of IoC. With qualifiers, it seems that the object is painfully aware not just of the existence of a container, but also how is that container configured exactly with qualifiers. This is no IoC.

Web applications typology

source

What follows is a nice, consise and accurate typology definition of otherwise

well-known concepts:

A web application is a dynamic extension of a web or application server. Web applications are of the following types:

Presentation-orientedA presentation-oriented web application generates interactive web pages containing various types of markup language (HTML, XHTML, XML, and so on) and dynamic content in response to requests.

Service-orientedA service-oriented web application implements the endpoint of a web service. Presentation-oriented applications are often clients of service-oriented web applications.

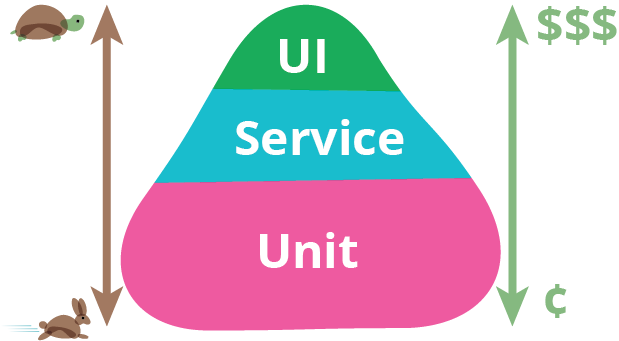

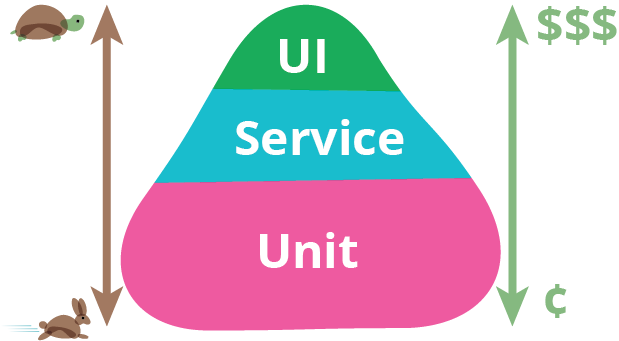

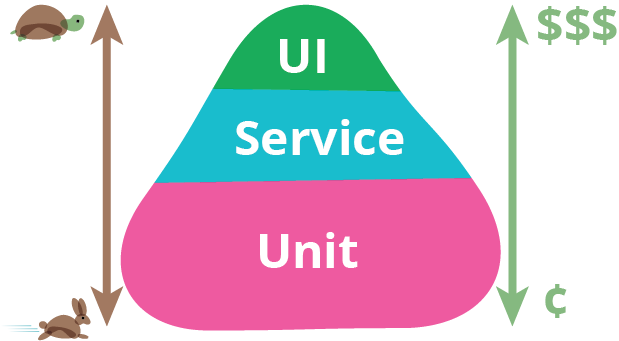

The test pyramid

source

The gist is that unit tests are fast and chep, recorded UI tests (e.g. with Selenium)

slow, brittle and expensive. Use an intermediate layer of testing just below UI

(subcutaneous tests) to avoid having brittle UI tests:

.

.

the gist of the Liskov substitution principle and the circle/ellipse problem (for practical purposes)

- the object-oriented inheritance paradigm is broken

- if you must use it, do not use inheritance (is-a relationships) when the

derived class restricts the freedom of the base class. So a Monkey is

an Animal but a Circle is not an Ellipse, a Square is not

a Rectangle and a Prisoner is not a Person. Given that in the

(pure) realm of Geometry a Circle is most assuredly an Ellipse and a Square is most

assuredly a Rectangle this reinforces the previous point.

- a more constructive takeaway is that mutability messes things up.

invariance, covariance and contravariance

Let f be a type transformation and let S (super) and D be types.

Further, let ≤ be the subclass relationship such that D ≤ S signifies that the derived

type D is a subtype of the S type.

Given the above definitions, we say that the transformation f is:

- invariant

- when D ≤ S does not imply that f(D) ≤ T(S)

- covariant

- when D ≤ S does imply that f(D) ≤ T(S)

- contravariant

- when D ≤ S does imply that f(S) ≤ T(D)

For a contravariance example in Java see here.

For invariance and covariance see my playground project here.

various type-system concepts

- Static type checking

- Dynamic type checking

- Type annotations

- Type inference

- Structural type systems

- Strong and weak type systems

- Type safety

- Memory safety

- Gradual typing

- Literal types

- Nullable and non-nullable types

- Union types

- Intersection types

- Dependent types

- Linear types

- Existential types

- Interfaces

- Polymorphism

On naming things

There is a practical consideration worth keeping in mind with names: they distinguish variables, functions and classes from each other.

As somebody said:

I found One Hundred Years of Solitude virtually incomprehensible because it features an enormous cast of characters whose names are all similar.

There is José Arcadio Buendía, José Arcadio, Arcadio, Aureliano José, 17 (!) other characters named Aureliano, José Arcadio Segundo and José Arcadio II (who is not Segundo),

Aureliano Buendía, Aureliano Segundo, Aureliano Babilonia, Aureliano II (again, different dude from Segundo), and Aureliano III.

Also Ursula Iguaran, Amaranta Ursula, and Amaranta.

Why JAXB is an unreliable technology

This unresponded, un-acknowledged bug report of mine from more than two (2) years ago should suffice to convince

all impartial observers: JIRA.

I created the JIRA bug report in frustration after this SO post of mine.

Logging strategy

2016-02-08

source

- DEBUG

- Log everything important with DEBUG level (but it shouldn't be too much, don't log 10MB data for each HTTP request).

INFOLog everything that happens in the system at a "higher" level with INFO level (like "add record with text {}").

WARN Log everything unusual with WARN level (like user validation failed). Log every unexpected but recoverable (application can serve other requests) error with ERROR level.

FATALLog unrecoverable error with FATAL level and shutdown application. Works fine for me.

TRACEAnd TRACE level just for debug, it's usually turned off, so it might produce any amounts of data.

Data Flow Analysis as a tool in understanding a domain

2016-02-05

source

Data-flow analysis was a method that was swept away (somewhat unfairly) on the grounds of being too procedural and not OO. One of its key tenets was that once you had discovered the essential flows and interactions, you should discard the problem-space partitioning that helped you find the graph, and use the graph to partition the solution space (which might well result in the same partitioning, but not always.)

XML is bad for distributed systems

2006-11-17

source

Dumb things about XML for distributed systems

I've been reading a lot of REST vs SOAP falderall lately and it's getting tiresome. Well, some of it is interesting, like looking at whether Bloglines is REST. Anyway, I thought I'd point out the cowman and the farmer can be friends, at least when we both are discussing the smell of the fertilizer. So, four dumb things about XML as a wire format for distributed systems:

- XML is text. You have to base-10 encode numbers in XML. This is terribly slow and inefficient.

- XML can't handle binary data. There is no reasonable way to embed a 400k image into your XML. Your choices are to base 64 encode it (whee!) or use some wrapper around the XML like MIME.

- XML is awfully wordy. I don't begrudge the meaningful beginning tag names and the pointy brackets, but the meaningful closing tag names are superfluous if all your XML is machine generated.

- XML is complicated. We love XML because it's S-expressions, but it's a lot more too. Entities! PIs (whatever those are). Attributes vs. elements! Three different ways to describe the data model! Awful programming models! It's awfully complicated when what you're trying to do is pass a couple of numbers and a string.

- The roots of XML are SGML, a hand-edited markup language for writing documents. I think it's clever that it's been repurposed for distributed systems, particularly since a human can easily read the packets without translation. And I really like the idea of document-oriented web services (whether SOAP or REST). But it'd sure be nice if the document were more friendly to computer data.

Why SOAP sucks for interoperable systems

2013-09-27

source

Why SOAP really sucks and is a bad choice for interoperable systems.

The promise of SOAP and WSDL was removing all the plumbing. When you look at SOAP client examples, they're two lines of code. "Generate proxy. RPC to proxy." And for toys, that actually works. But for serious things it doesn't. I don't have the space to explain all the problems right now (if you've seen my talks at O'Reilly conferences, you know), but they boil down to massive interoperability problems. Good lord, you can't even pass a number between languages reliably, much less arrays, or dates, or structures that can be null, or... It just doesn't work. Maybe with enough effort SOAP interop could eventually be made to work. It's not such a problem if you're writing both the client and the server. But if you're publishing a server for others to use? Forget it.

The deeper problem with SOAP is strong typing. WSDL accomplishes its magic via XML Schema and strongly typed messages. But strong typing is a bad choice for loosely coupled distributed systems. The moment you need to change anything, the type signature changes and all the clients that were built to your earlier protocol spec break. And I don't just mean major semantic changes break things, but cosmetic things like accepting a 64 bit int where you use used to only accept 32 bit ints, or making a parameter optional. SOAP, in practice, is incredibly brittle. If you're building a web service for the world to use, you need to make it flexible and loose and a bit sloppy. Strong typing is the wrong choice.

The REST / HTTP+POX services typically assume that the clients will be flexible and can make sense of messages, even if they change a bit. And in practice this seems to work pretty well. My favourite API to use is the Flickr API, and my favourite client for it is 48 lines of code. It supports 100+ Flickr API methods. How? Fast and loose. And it works great.

To be fair, SOAP can be forced to work. Using SOAP didn't really hurt adoption of the APIs I worked on. But it sure didn't help either. So what's the alternative? I'm not sure. Right now I'd probably go the HTTP+POX route while trying to name my resources well enough that the REST guys will invite me to their parties. But XML itself is such a disaster and AJAX is starting to show the cracks in HTTP (like, say, the lack of asynchrony).

Verification -vs- Validation

2013-09-26

Not to mention the fact that unit tests can only help with verification - i.e.

that you have built the software to expectations and to catch regressions.

I would say that 90% of the grief I have experienced building applications is

the validation part - that you are actually building the right thing.

On productivity and estimating software schedules.

2013-09-19

The difference in programmer productivity can vary by a factor of 80 - (really it's infinity,

because some programmers *never* get some code right, so the factor 80 discounts the

totally failed efforts) - So given a productivity factor you have to normalize it by a factor

that depends upon the skill and experience of the programmer.

There are people who claim that they can make models estimating how long a software projects take.

But even they say that such models have to be tuned, and are only applicable to projects

which are broadly similar. After you've done almost the same thing half a dozen times

it might be possible to estimate how long a similar project might take.

The problem is we don't do similar things over and over again. Each new unsolved problem

is precisely that, a new unsolved problem.

Most time isn't spent programming anyway - programmer time is spent:

- fixing broken stuff that should not be broken

- trying to figure out what problem the customer actually wants solving

- writing experimental code to test some idea

- googling for some obscure fact that is needed to solve a) or b)

- writing and testing production code

e) is actually pretty easy once a) - d) are fixed. But most measurements of productivity only measure

lines of code in e) and man hours.

Pike on programming

201X-00-00

It is not usually until you've built and used a version of the program

that you understand the issues well enough to get the design right.

—Brian Kernighan, Rob Pike, The Practice of Programming

ORMs suck

ORMs start easy and simple, but lack various features of full SQL. If you start a new project, the ORM is fine.

At some point, you are forced to use plain SQL, which clashes horribly with the ORM concepts.

Thus the desire to extend the ORM. Over time more and more features are bolted on and the complexity grows.

Why OSGI sucks

2011-03-22

It is very very hard to find opinions of what might be “not so great” about OSGi, or reasons that hinder it’s adoption. It’s even harder to find that kind of info from insiders who truly know OSGi by heart.

Most criticism is received with flames, so most times it isn’t even worth it to comment on critical posts, attracting flamers.

As a thank you for your article I want to live you this comment from a complete ousider to OSGi, who has been keeping it under watch for 2 years now. Perhaps you might find it somehow useful, o rperhaps you might give me some more insight on the value that I’m missing:

The reasons why I’ve passed on adopting OSGi as the core for developing software at my software company, are:

First of all, we are a software company that develops, deplyos and supports software as solutions, for telcos.

To us, modularity is not a goal on it’s own. It’s a means to an end. ?what end? The technical benefits achieved by it, you know them. So at least for my company the issue is that the extent to which we might need those benefits afforded by OSGi’s modularuty (like being able to deploy and kill individual runtime components, downsize or grow footprint, etc) is not large enough for us to want to pay for it’s full price (more on the price later).

For isolation from other solution provider’s systems we just reside on our own JVM, in its own server. For provisioning of resources, said server can be virtual. To integrate with third parties, SOA does the deal without putting us all in the same bed (JVM). And this is not for a technical reason but a business reason: ?coexisting with oter vendor’s software on the same JVM? ?Having to demonstrate to the customer that OutOfMemory Exceptions or excessive CPU consumption is due to that other vendor?. It’s not an attractive proposition unless we could charge lot for that feature, but the customer won’t pay more for it, and they probably already payed VMWare to solve that kind of problems. Of course there is also “internal” isolation of our own modules from each other. However, as an architect I don’t see isolation “beyond what can be done with packages” as something I want whithin my own product. I don’t want people reinventing wheels, nor pointing fingers at each other. I want a collaborative culture, and a framework that forces isolation within my product into isles is not something I really want. I am an agilist, and thus a believer in not applying technical fixes to cultural problems.

About the feature of restarting individual components, we already deal with it, since redundant servers (needed by HA) allow us to make said restarts without much detriment to end users, and our customers are OK with it. OSGi could make us more dynamic on this, yes, and more fine-grained, but we are “just fine” as is. I reckon many other software developers don’t have this luxury and could profit from OSGi, just not us.

About managing the complexity of dependencies, our software is in the thousands of classes and 40 MB in libraries, yet for us, Java’s own classloader is still enough to deal with dependencies, and this -as I see it- is because the whole set of “what goes into the classpath” is under our control as the Software vendor with on-site support of the app in production, so we can just apply a tried-and-true-and-cheap way to keep a system that uses a lot of dependencies stable: stay with the versions of the libraries that are known to work, and not update any until we need a feature in the newer version that is worth the cost of spending time to evaluate that newer version and change our code to support it. This approach just works. We can stay a whole year with an old version of a library, yet the customer is happy, and it’s not hard to keep the versions of libraries synchronized between our dev servers and the customers test and production servers. I belive in this regard that OSGi is a great technology that would make much more sense as a core for an IT department that needs to integrate software that it subcontracts from various providers (such as small companies and/or freelancers), or by company with a really really huge project.

OSGi could allow us to be more dynamic in handling dependencies, but for us, the co$t of the “issue of dependency management of third party libraries” gravitates more around analyzing, reading, testing, experimenting, and being sure the whole system will still work, which are labor-intensive areas in which OSGi does not provide significant savings. Testing frameworks and JUnit provide the value we need here. And regarding dependency management inside our own software, continuous integration and automated testing provides the kind of confidence we need in the “working solution”. I see some value on OSGi here but not enough for the price.

So there are good things to be had with OSGi. It’s just that once you have invested in solutions for the issues OSGi solves, your existing solutions might be technologically inferior, but they appear as free. OSGi, on the other hand appears with an apparent price of a “steep learning curve”, stone age Java language (some OSGi advocates dare say “in very few cases are the features of java 5 useful”, no comments), and a need for an app-wide migration, which I fear I wont be able to sell to management, given how hard it is to sell them refactoring efforts (for quality and maintainability).

If I was just comming to the business of software in 2010, OSGi would be my choice. But given what I currently already have, It’s a business proposal thats not that bad, but not good enough for me to bet company money and/or carreer prospect on it.

please remember that I’m trying to criticize or denigrate from OSGi. I’m just trying to express why guys like me run away scared.

GUIs suck, CLIs rule

This is dead on. Human beings invented symbolic language because it's simply more expressive than pointing and grunting. CLIs are superior to GUIs for the same reason.

Bottom-up and top-down

It can be a partially bottom-up and partially top-down process

RPC is bad

Abstract

I personally think that all forms of RPC are way over-hyped, and not actually terribly useful in the majority of situations in which you'd be tempted to use them. I know this is an unusual point of view, and needs justification.

Background

As a broad outline, you can plot different forms of IPC on a graph with one axis being speed, and the other coupling or, it's inverse, portability. Speed and coupling, like space and time complexities in algorithms, can be related, but, IMHO, are largely orthogontal.

How the axis of the graph are related to real-world protocols.

For example, one naive form of IPC that I've seen commonly is for raw memory to be dumped onto a socket or a pipe. This is great for speed, but very bad for coupling (i.e. very non-portable). It might not even work for two different compilers on the same platform, and if you're trying to communicate between two different languages, each program needs to know intimate details about how the other lays things out in memory. Also, naively implemented, with little thought given to minimizing round-trip requests, it often isn't as fast as you'd think. (More on that later).

At the opposite corner in the graph are protocols like SMTP, or even worse, XML over HTTP. SMTP communicates using text messages that have to be parsed. SMTP parsing is pretty simple, although, looking at sendmail, it can get pretty hairy. XML parsing is even more complex. These parsing steps slow things way down. On the other hand, the well defined nature and robust structure of these protocols makes them extremely portable (i.e. low coupling).

So, where does RPC fit into all of this?

In my opinion, CORBA, and other RPC solutions are medium to highly coupled, and medium to low speed. Not as bad on speed as, perhaps, XML, but not all that great either.

Justification

Medium to high coupling

Well, if you think about it, all forms of RPC, including CORBA, require a fairly explicit detailing of the messages to be sent back and forth. You have to specify your function signature pretty exactly, and the other side has to agree with you. Also, the way RPC encourages you to design protocols tends to create protocols in which the messages have a pretty specific meaning. In contrast, the messages in the SMTP or XML protocol have a pretty general meaning, and it's up to the program to interpret what they mean for it. This bumps RPC protocols up on the coupling scale a fair amount, despite the claims of the theorists and marketers.

OTOH, the messages are platform and language independent. It's relatively easy to find a binding for any given language. Usually the code to decode the message from a bytestream and call your function is generated for you. And, the bytestream will be the same if you get your message from a perl program or a C++ program. This bumps it down on the coupling scale from the memory dumping protocols.

Medium to low speed

Marshalling

This one is minor in that almost any protocol that is supposed to be language and platform independent is going to have it. The problem is marshalling. You have to get your data from the format your language keeps it in into your wire format and back again. While this problem is not as computationally intensive as parsing, it still exists.

Overly synchronous

The other is major. The one thing you always want to avoid in any networking protocol is round trip requests. Round trip requests will always be inherently slow, if for no other reason than the speed of light. You never want to wait for your message to be processed, and a reply sent before you send another message. The X protocol works largely because it avoids round-trip requests like the plague. There is a noticeable lag when an X program starts up because the majority of the unavoidable round trip requests (for things like font information and a bunch of window ids and stuff) are made then. Even when the programs are on the same computer, round trip requests force context switches which eat CPU time. In short, they are BAD.

Any RPC oriented protocol encourages you to think of the messages you are sending as function calls. In every widely used programming language, functions calls are synchronous. Your program 'waits' for the result of a function call before continuing. This encourages thinking about your RPC interface in entirely the wrong way. It doesn't make you focus on the messages you're sending, and the inherently asynchronous nature of such things. It makes you focus on the interface as you would a normal class interface, or a subsystem interface. This leads to lots of round-trip requests, which is a major problem.

CORBA generally advocates soloving this problem by making heavy use of threading. But multiple threads have a lot of problems. They just move the descisions about handling asynchronous behavior to the most difficult part of your program to deal with it in, your internal data structures. Not only that, but multiple threads are a big robustness problem. It's difficult to deal with the failure of a single thread of a multi-threaded program in an intelligent way, especially if the job of that thread is intimately intertwined with what another thread is doing.

Also, threads end up taking up a lot of resources. Both obvious ones like context switches and space for processor contexts, and in less obvious ones, like stack space. One program I saw had a thread for every communcations stream, and it needed to deal with over 300 streams at a time. It also needed a stack of 1M for each thread because some function calls ended up being deeply nested. That's at least 300M just for stack space. The program may have had no difficulty dealing with 300 communications streams at once had it not used threads. As it was, it constantly ran out of memory.

Conclusions

In short, CORBA, and other RPC solutions look like a quick and easy answer to a difficult problem, but, measured on the coupling and speed scales, they are medium to highly coupled, and medium to low speed. Not as bad on speed as, perhaps, XML, but not all that great either.

Grand dreams of utopia

I would like to see (and am in the process of creating) a very message oriented tool for building communications protocols. It would concentrate heavily on what data the messages contained, not what the expected behavior of a program receiving the message should be. It would be supported by a communcations subsystem that emphasized the inherently asynchronous nature of IPC, and made it easier to build systems that used that to provide efficient communcations. It would provide auto-generated marshalling and unmarshalling of data, and even a provision for fetching metadata describing unkown messages, much like XML. It would also allow you to easily override the generated functions with your own functions that are tuned to the data you're sending. It would also make it easy to build and layer new protocols on top of existing ones, or transparently extend protocols in such a way that old programs would still work.

As a last note, I would like to say that we've known for years how to handle the inherently asynchronous nature of user interaction. All of our UI libraries are heavily event oriented. Processing is either split up into small discreet chunks that can be handled quickly inside an event handler, or split off into a seperate thread that communicates to the main program mainly through events. We need the same kind of architecture for programs that do IPC.

If anybody is interested in the beginnings of such a system, I have an open source project that I think is still in the 'cathedral' stage. I would like help and input on its development though, and I need help making it easy to port and compile in random environments. If you would like to help, please e-mail me. I call the system the StreamModule system, and it's architecturally related to the idea of UNIX pipes, and the System V STREAMS drivers.

.

.

.

.